Population & Migration

Australia’s National Population Dynamics

Key Points

- The latest official data show an annual population increase of 423,400 over the year to March 2025, taking Australia’s population to 27,536,900. This was made up of 107,400 of natural increase and t316,000 in net migration

- Australia’s population growth appears to be normalised following the recent surge but the new normal population growth and immigration numbers are likely to be higher than government projections

- Australia has now fully regained the population it lost as a result of the pandemic despite key infrastructure development failing to keep pace

- Was seeking a return to the 1.5% growth trajectory a sensible policy approach given the capacity constraints the economy is facing?

- If we had targeted a 1.2% population growth trajectory over the last three years the current population would be 300,000 lower, which could have limited housing shortages and congestion

Narrative

Recent immigration indicators suggest that population growth will pick-up once again in FY26.

The latest data show an annual increase in Australian population of 423,400 people over the year to March 2025, taking Australian population to 27,536,900. This was made up of 107,400 of natural increase and the other 316,000 is Net Overseas Migration (NOM).

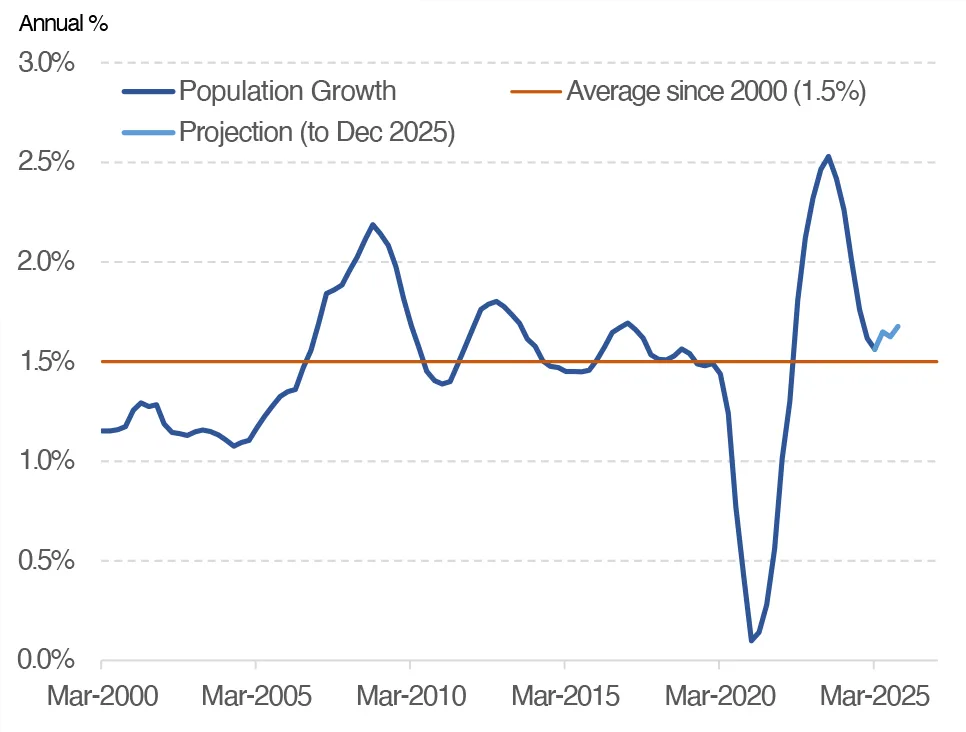

Australian population growth was 1.56% in the year to March 2025, the lowest rate since the population surge that commenced after the election of the federal ALP government in 2022. The surged resulted in a ‘peak’ population growth rate of 2.5% in September 2023. Population growth of 1.5% is in line with the outcomes prior to the pandemic. The average annual population growth over the first 25 years of the 21st century is 1.5%.

The March quarter result was strong, in line with higher frequency data such as the monthly overseas arrivals and departures data. NOM in the March Quarter was +110,100, well up on the +66,100k in the December quarter and higher than the average increase of about +70,000 over the previous nine months.

NOM is highly seasonal, with the March quarter accounting for about one third of the annual intake each year. Even once this is accounted for, the March quarter data (and other higher frequency indicators more recently) suggest annual population growth will start heading higher over the next year, possibly reaching annual growth of 1.8% in early 2026.

To give some context:

In FY23 population growth hit a record high of 614,000 followed by a still high 533,000 in FY24.

Last year (FY25) population increase looks like being 455,000 and this year (FY26) is expected to be 450,0000.

Prior to the pandemic population growth was usually somewhere between 350,000 and 400,000.

The stronger population growth outcomes and our projections are in contrast to the forecasts released by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) in their August Statement on Monetary Policy, as well as those presented by the Federal Treasury in the March Budget.

These official projections from the Federal Treasury play a significant role in strategic planning, as they are used as a foundation for state and territory government policies, as well as by numerous major organisations when making decisions regarding investment and future planning.

Australia’s population growth appears to be normalised following the recent surge but the new normal population growth and immigration numbers are likely to be higher than government projections or the experience prior to the pandemic.

Population Recovers: The New Normal?

Narrative

According to the most recent data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australia has now fully regained the population it lost as a result of the pandemic. The concept of ‘population loss’ is determined by comparing the actual population figures to those projected under a scenario of continued ‘normal’ growth, which we assumed to be an annual rate of 1.5%—the average experienced over the previous 25 years.

Following severe restrictions on people movements through the pandemic of 2020 and 2021, the Coalition government decided to restore immigration rates back to pre-pandemic levels (approximately 235,000 a year) in late 2021.

This was a deliberate decision not to ‘catch-up’ the lost population after 2 years of restrictions on people flows into and out of Australia. If we had remained on this (Coalition) path, we would have ‘locked in’ a permanent loss of population of about 600,000 people (compared to previous Treasury expectations and revenue projections).

During the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, Australia imposed stringent restrictions on the movement of people, both into and out of the country. In response to these unprecedented circumstances, the Coalition government made the decision in late 2021 to restore immigration rates to pre-pandemic levels, setting an annual target of approximately 235,000 people.

This policy was a conscious choice not to pursue a ‘catch-up’ strategy to make up for the population shortfall caused by two years of limited migration. Had the Coalition approach continued over the last 3 years, Australia would have effectively locked in a permanent population loss of around 600,000 people. This figure is significant when measured against prior Treasury expectations and revenue forecasts.

Following the election victory in 2022, the federal ALP government commencement a program of catch-up, likely with strong support from Treasury officials, with the aim of restoring Australia’s population numbers back onto a 1.5% (or similar) growth trajectory.

Following its electoral victory in 2022, the federal Labor (ALP) government initiated a targeted programme designed to ‘catch up’ on Australia’s pandemic-related population shortfall. This approach was likely developed in close consultation with Treasury officials, reflecting a shared objective to return the nation’s demographic growth to its pre-pandemic trajectory.

Net overseas migration over the three years to March 2025 has been 1,305,000, which compared to the March 2022 total population of 25,913,000 implies a 5% increase in Australia’s population over the last three years from immigration alone.

In contrast, natural increase over the same three-year period has been 318,300; a 1.2% population increase.

Over the three-year period leading up to March 2025, net overseas migration has played a significant role in Australia’s population catch up. During this time, net overseas migration contributed 1,305,000 people to the population. When compared to the total population of 25,913,000 in March 2022, this represents a 5% increase in the nation’s population solely attributable to immigration.

By contrast, the natural increase—defined as the difference between births and deaths—accounted for a much smaller portion of the population growth over the same period. The natural increase added 318,300 people, corresponding to a 1.2% rise in population. This comparison highlights the dominant influence of net overseas migration on Australia’s recent demographic trends, with immigration outpacing natural increase as the primary driver of population growth between 2022 and 2025.

This is the new normal. Up until about 25 years ago, the contribution to population growth from net immigration was rarely bigger than natural increase. But as Australia’s fertility rate declines, immigration is the only real lever that can be pulled to boost overall population growth.

This raises several issues and policy questions for Australia over the years ahead.

Was maintaining a 1.5% growth rate a sensible policy approach given the capacity constraints the economy is facing? Did the pandemic impact our ability as a nation to create new capacity? This implies a policy to restore population growth might be considered unwise if the infrastructure is not in place to take on new people.

The most obvious issue is housing where excess demand (dwelling supply shortages) are being blamed for the worst housing affordability issue in Australia’s history.

There are other capacity constraints emerging in general infrastructure (congestion) and the health care system (ramping, for example).

The chart below highlights that if we had of targeted 1.2% population growth over the last three years the current population would be 300,000 lower. Ironically this is about half what the Coalitions approach would have produced, that is, a population level about 600,000 lower than what we have now.